Real data#

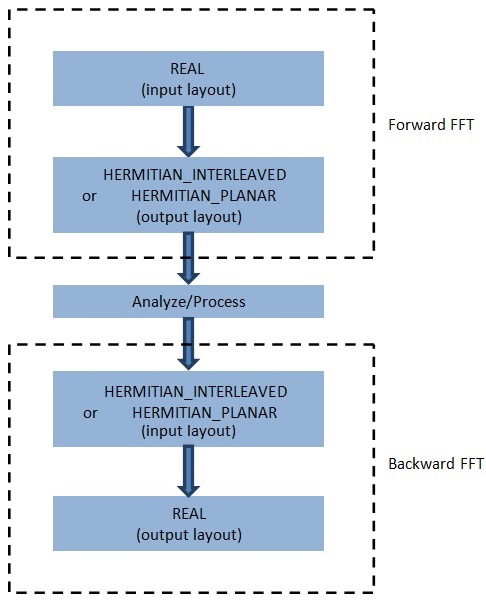

When real data is subject to DFT, the resulting complex output data follows a special property. About half of the

output is redundant because they are complex conjugates of the other half. This is called the Hermitian redundancy. So, for space

and performance considerations, it is only necessary to store the non-redundant part of the data. Most FFT libraries use this property to

offer specific storage layouts for FFTs involving real data. rocFFT

provides three enumeration values for rocfft_array_type to deal with real data FFTs:

REAL (

rocfft_array_type_real)HERMITIAN_INTERLEAVED (

rocfft_array_type_hermitian_interleaved)HERMITIAN_PLANAR (

rocfft_array_type_hermitian_planar)

The REAL (rocfft_array_type_real) enum specifies that the data is purely real. This can be used to feed real input or get back real output. The

HERMITIAN_INTERLEAVED

(rocfft_array_type_hermitian_interleaved) and HERMITIAN_PLANAR (rocfft_array_type_hermitian_planar) enums are similar to the corresponding full complex enums in the way

they store real and imaginary components, but store only about half of the complex output. Client applications can do just a

forward transform and analyze the output or they can process the output and do a backward transform to get back real data.

This is illustrated in the following figure.

Fig. 1 Forward and Backward Real FFTs#

Note

Real backward FFTs require that the input data be Hermitian-symmetric, as would naturally happen in the output of a real forward FFT. rocFFT will produce undefined results if this requirement is not met.

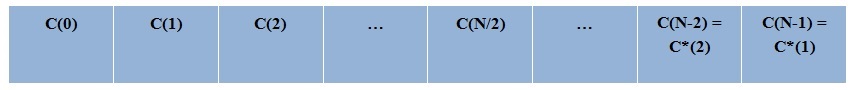

Let us consider a 1D real FFT of length \(N\). The full output looks as shown in following figure.

Fig. 2 1D Real FFT of Length N#

Here, C* denotes the complex conjugate. Since the values at indices greater than \(N/2\) can be deduced from the first half of the array, rocFFT stores data only up to the index \(N/2\). This means that the output contains only \(1 + N/2\) complex elements, where the division \(N/2\) is rounded down. Examples for even and odd lengths are given below.

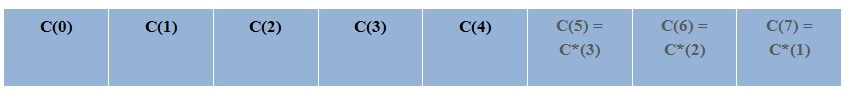

Example for \(N = 8\) is shown in following figure.

Fig. 3 Example for N = 8#

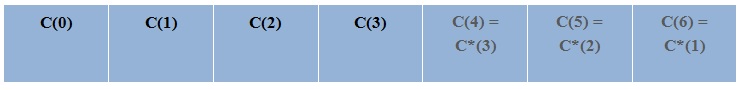

Example for \(N = 7\) is shown in following figure.

Fig. 4 Example for N = 7#

For length 8, only \((1 + 8/2) = 5\) of the output complex numbers are stored, with the index ranging from 0 through 4. Similarly for length 7, only \((1 + 7/2) = 4\) of the output complex numbers are stored, with the index ranging from 0 through 3. For 2D and 3D FFTs, the FFT length along the innermost dimension is used to compute the \((1 + N/2)\) value. This is because the FFT along the innermost dimension is computed first and is logically a real-to-hermitian transform. The FFTs along other dimensions are computed next, and they are simply ‘complex-to-complex’ transforms. For example, assuming \(Lengths[2]\) is used to set up a 2D real FFT, let \(N1 = Lengths[1]\), and \(N0 = Lengths[0]\). The output FFT has \(N1*(1 + N0/2)\) complex elements. Similarly, for a 3D FFT with \(Lengths[3]\) and \(N2 = Lengths[2]\), \(N1 = Lengths[1]\), and \(N0 = Lengths[0]\), the output has \(N2*N1*(1 + N0/2)\) complex elements.

Supported array type combinations#

Not In-place transforms:

Forward: REAL to HERMITIAN_INTERLEAVED

Forward: REAL to HERMITIAN_PLANAR

Backward: HERMITIAN_INTERLEAVED to REAL

Backward: HERMITIAN_PLANAR to REAL

In-place transforms:

Forward: REAL to HERMITIAN_INTERLEAVED

Backward: HERMITIAN_INTERLEAVED to REAL

Setting strides#

The library currently requires the user to explicitly set input and output strides for real transforms for non simple cases. See the following examples to understand what values to use for input and output strides under different scenarios. These examples show typical usages, but the user can allocate the buffers and choose data layout according to their need.

Examples#

The following figures and examples explain in detail the real FFT features of this library.

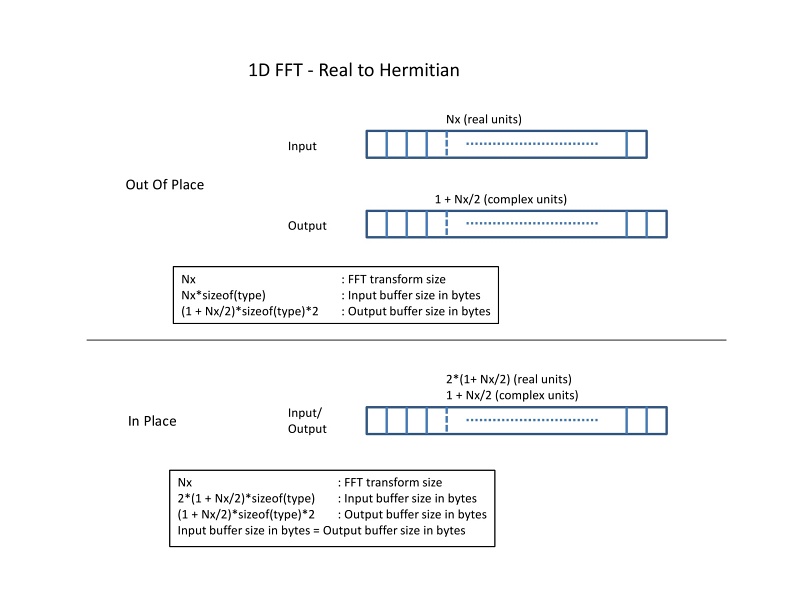

Here is a schematic that illustrates the forward 1D FFT (real to hermitian).

Fig. 5 1D FFT - Real to Hermitian#

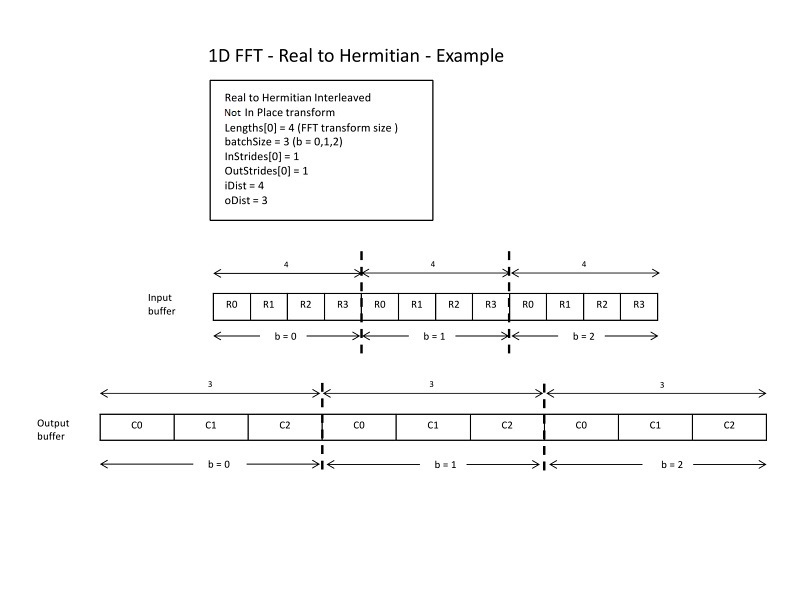

Below is a schematic that shows an example of not in-place transform with even \(N\) and how strides and distances are set.

Fig. 6 1D FFT - Real to Hermitian, Example 1#

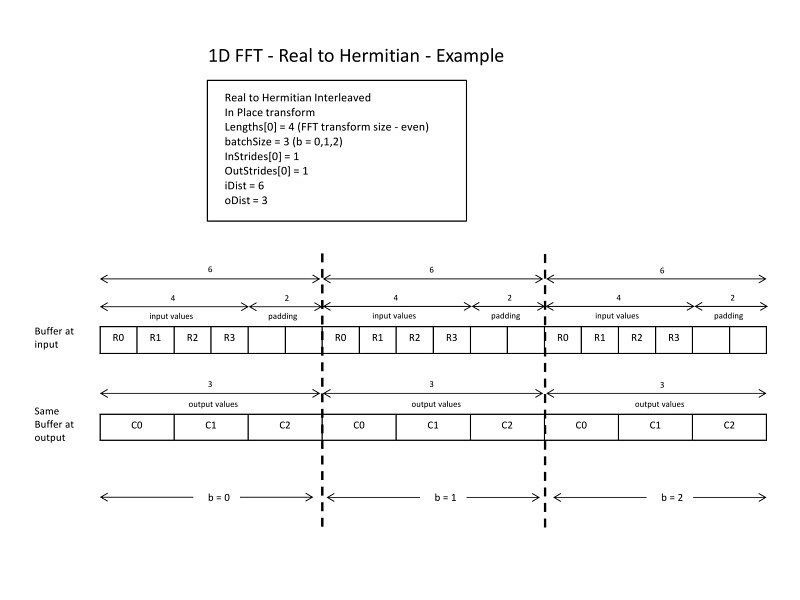

Below is a schematic that shows an example of in-place transform with even \(N\) and how strides and distances are set. Notice that even though we are dealing with only 1 buffer (in-place), the output strides/distance can take different values compared to input strides/distance.

Fig. 7 1D FFT - Real to Hermitian, Example 2#

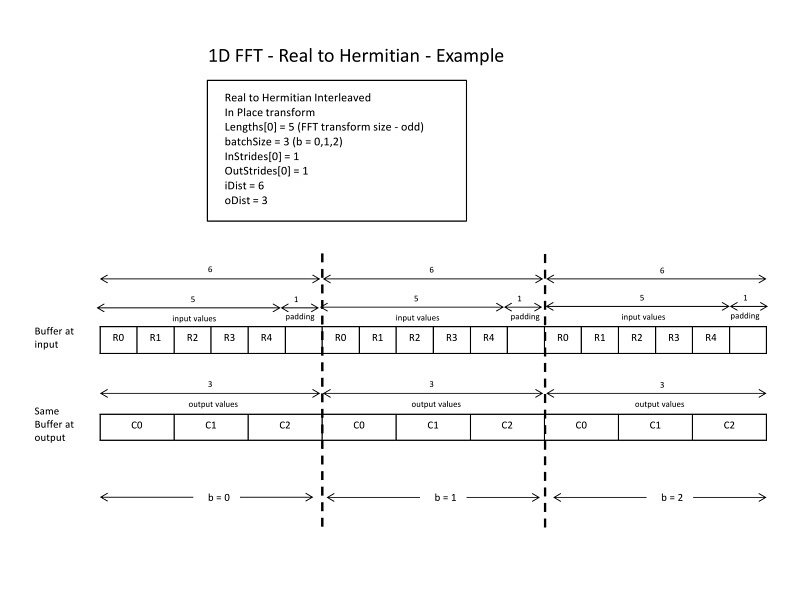

Below is a schematic that shows an example of in-place transform with odd \(N\) and how strides and distances are set. Notice that even though we are dealing with only 1 buffer (in-place), the output strides/distance can take different values compared to input strides/distance.

Fig. 8 1D FFT - Real to Hermitian, Example 3#

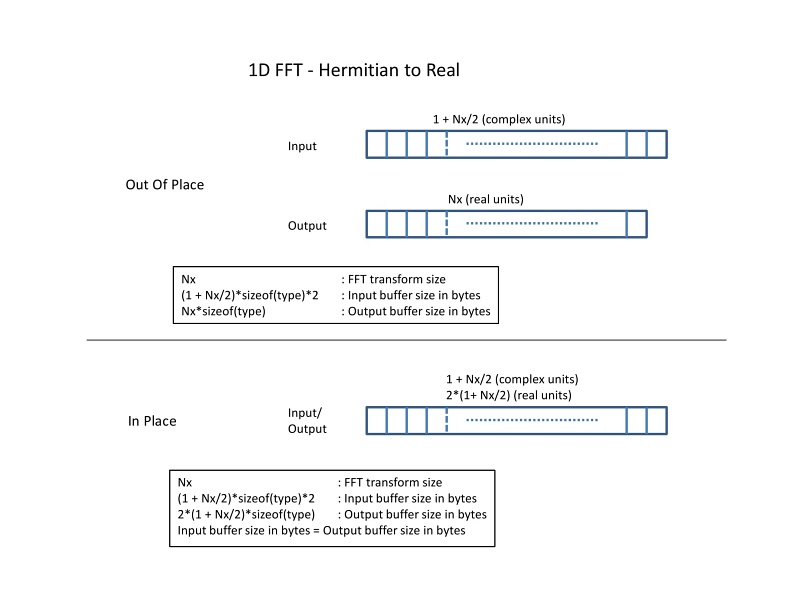

And here is a schematic that illustrates the backward 1D FFT (hermitian to real).

Fig. 9 1D FFT - Hermitian to Real#

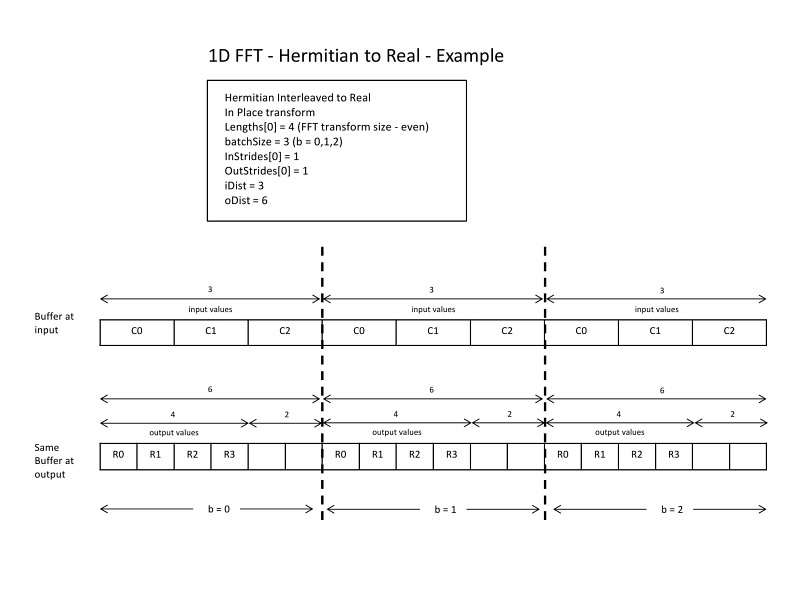

Below is a schematic that shows an example of in-place transform with even \(N\) and how strides and distances are set. Notice that even though we are dealing with only 1 buffer (in-place), the output strides/distance can take different values compared to input strides/distance.

Fig. 10 1D FFT - Hermitian to Real, Example#

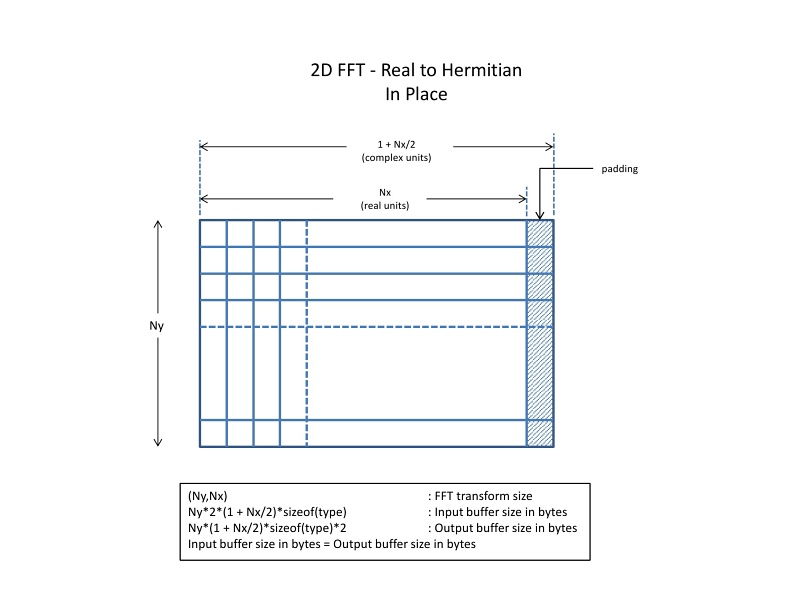

And here is a schematic that illustrates the in-place forward 2D FFT (real to hermitian) .

Fig. 11 2D FFT - Real to Hermitian In Place#

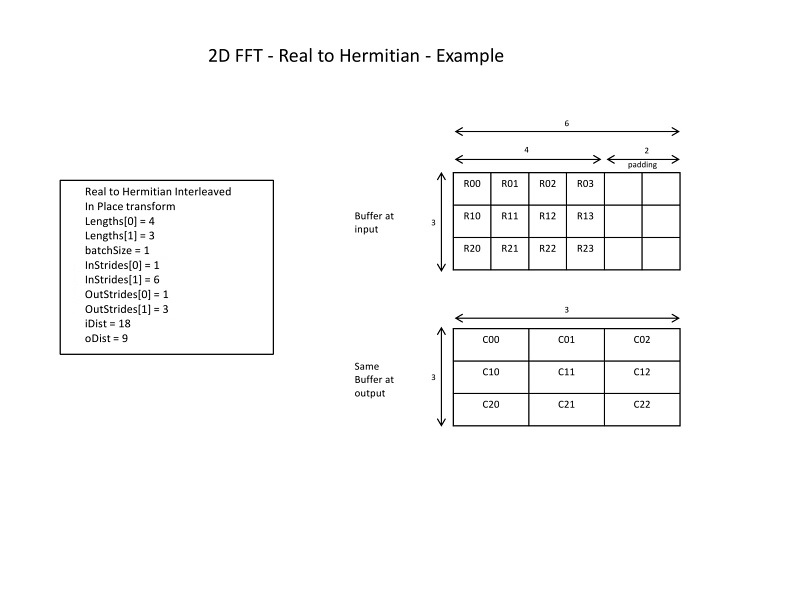

Below is a schematic that shows an example of in-place 2D transform and how strides and distances are set. Notice that even though we are dealing with only 1 buffer (in-place), the output strides/distance can take different values compared to input strides/distance.

Fig. 12 2D FFT - Real to Hermitian, Example#